Ashok Mukhopadhyay

[1]

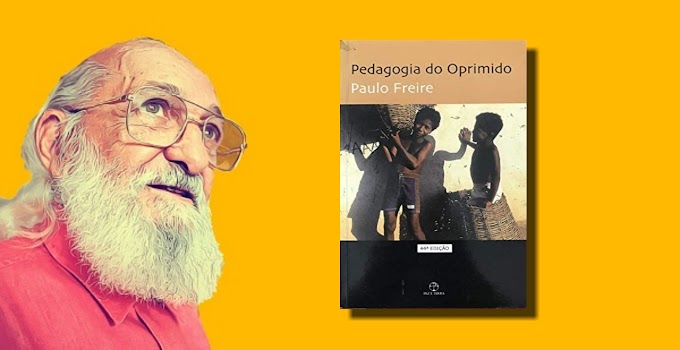

To be honest, I didn't know anyone named Peter Hudis until a few days ago. Naturally, If you study within a very narrow scope, it is not possible to get the name and work of many people in the world of knowledge. A few days ago I found him out by accident.

A letter came to me from a friend of mine, the editor of a left-wing bimonthly. It mentioned an author called Peter Hudis who had written an essay – "Karl Marx among Muslims". It came out in the journal Capitalism Nature Socialism Vol. 15, No. 4, in 2004. The English article was recently translated into Bengali by Comrade Malay Tewari. I got to know the name of Hudis by virtue of that article. I went to the original source and read the original article.

The first few pages were quite enjoyable to read. The author states that some aspects of Marxian and Hegelian dialectics were raised by some lesser-known philosophers in non-European regions some time ago. Abu Yaqub al-Sijistani, a philosopher of the Ismaili Islamic sect of Iran in the 10th century, in explaining the perception of God, gave birth to such an idea of negation of negation. Perhaps, this was the first philosophical formulation of “the negation of negation” eight hundred years before Hegel.

But I would like to raise two objections in this context.

One, from what Hudis quotes from the works of this Muslim thinker, it appears that Sijistani meant negation and negation rather than negation of negation. A statement that refutes an idea must also be refuted in the next step -- as Sijistani's point was. However, only a person familiar with the history of philosophy will understand that, although it resembles the Hegelian lexicons, it does not carry or indicate exactly the same meaning in a philosophical context. That is, it is more akin to Aristotelian formal logic. A cat is not a dog, not only a dog, but also not a tiger. Much like this.

Second, the Hegelian as well as the Marxian negation of negation (as I have shown in my work on philosophy) indicates the different stages of a dynamic and changing process. Although Hegel himself was an idealist, he used real-world examples to illustrate this principle. Marx and Engels also applied this formula to various socio-economic and natural developmental phenomena. Judging from that point of view, Sijistani's statement -- at least as far as I can find in Hudis' writings -- does not involve any transformative events. It relates to a certain or fixed idea.

In view of these two aspects, it is easy to see that the concept of negation in Sijistani's philosophy was in no way intertwined with dialectical thought, whether as negation of negation or as negation and further negation - however he had viewed it. Nevertheless, to be able to think this way in the tenth-century philosophy is undoubtedly an advance.

[2]

After that, from the third section I started to recognize which camp of thought Hudis represents. Then I felt an urge to say something more.

Recently, a new kind of obsession has started as regards Karl Marx. In the 1960s and 1970s, we had seen a group of Western Marxiologists often make a comparative judgment between the young Marx and the late Marx, and they gave the young Marx higher grades in terms of breadth of thought. The mature Marx had lost the critical revolutionary appeal in his concern for man’s emancipation in the narrow atmosphere of party politics and in the routine programmes of class struggle. It was a familiar discourse in college classrooms and academic seminars. In recent times, especially since the fall of the socialist camp, a new genre of rock music is in circulation about the so-called mature Marx. Since the 1990s, based on the recent initiative for the publication of the Marx-Engels Gesamtausgabe (abbreviated as the MEGA project), a group of Marxist researchers have been claiming that the Soviet Union, following Engels, Plekhanov, Lenin, and Stalin, promoted Marx's thought as a mechanistic, rigorously disciplined scientific doctrine called Marxism. And it was an inviolable replica of European social history. As the new works of Marx are made available, it is clearly seen that Marx's thinking was not like that. etc.

I found that the author of the above essay, Peter Hudis, is also one of the staunch exponents of this reading of Marx.

What is their theme song?

This group of neo-experts tries to show that most of the books that Marx consciously wrote and published during his lifetime were rubbish, and did not reflect Marx's true thoughts. But all the notes that Marx made at different times to be published in the form of future books, or the comments that he wrote in the margins of various books, are all priceless gems. For example, the various draft notes on political economy written in 1857-63, parts of which formed the later work titled Capital, and another part of which published much later as the Grundrisse, are a gold mine. For example, in 1880-81, notes written in various copy-books reveal the original Marx, etc. This is a very surprising Marx study. What is more surprising is that many Marxists in different countries of the world, even the political activists in the field, do not understand the true nature of this research. They are also fascinated by the discoveries of the new manuscripts of Marx! We have been so blind for so long. They do not see the terrible shock befalling the practice of Marxism.

Let us give some examples.

Consider Marx's conception of the Asiatic mode of production. As we know, Marxist historiography shows a general sequence of social development as follows: primitive communist society, slavery, feudalism, capitalism, socialism, etc. It is true that this description is mostly true for some countries in Western Europe. It cannot be fully reconciled with the development of the long history of other countries, not only in Asia or Africa, but even in Europe. Therefore, whether consciously or unconsciously, Marxists look to this account as a model to explain their own country's history.

But that does not mean that we have to set up a new model for non-European countries. If we talk about the Asiatic mode of production, the question will obviously arise: Was that system also the same in China and India? Was there a single type of production system in the Arab land and in Malaysia? We know that it was not. And it can be easily understood. So, in showing the development of Marx's non-European thought, can we go even one step further by raising the issue of Asiatic mode of production? What is the gain?

There are more problems.

In Marx's view, a specific socio-economic system is characterized by the extant relations of production, in terms of class division. Whether a country has irrigation or not does not determine the character of the historical stage of its production. This simple fact is either forgotten or denied by our neo-Marxist experts. Peter Hudis is no exception. Again, it is in the light of these relations of production that one can understand how the owning class collects surplus from the real producers. We know the methods of surplus extraction under slavery, feudalism and capitalism. If we want to show the Asiatic mode of production as a different economic system, it is necessary to identify what is the modality for realizing the surplus there – as different from the other three social structures. Unfortunately, no light has been found on this subject in Marx's writings. Our current MEGA-expert scholars have also failed to shed any light in this regard. Or maybe, they are not even aware that this work has to be done.

Nay, I suspect, these neo-scholars perhaps no longer consider Marx's analysis of class, the nature of class struggle, etc. as Marx's Marxism. These are the “pseudo-Marxism” of Engels, Plekhanov, Lenin, Stalin, and so on. The "real Marx" moved away from the unilinear class analysis of European societies and dived into the sea of multilinear sociocultural analysis of non-European societies. In various notes, in the margins of many books, he wrote down all those words hideously (probably out of fear of Engels). Marx's thought must now be recognized by recovering all those notes.

Take, for example, Marx's words: "According to Indian law the ruling power is not subject to division among the sons; thereby a great source of European feudalism [is] obstructed." [Cited, Hudis 2004]

The question is, where did Marx get this idea from? If only he had read the Ramayana and the Mahabharata (assuming Marx had some ideas about them), he would have seen that the narratives of these two great epic had developed and were fuelled by stories of quarrels and fights among the kith and kin over how to divide rulership and royal estates among the sons of brothers. In all the known kings of Indian history, there was a rigid custom of inheritance of the throne along the line of sons. Kings wanted sons from their queens. The Sanskrit dictum was – ‘putrarthe kriyate varyya’ (that is, wife is taken for begetting sons). For a married woman the greatest blessing of the elders was – ‘be the mother of a hundred sons’. No, there was no demand for daughters. So, in this question at least, feudalism in India was no different from that of Europe. If for some reason Marx didn't know this factuality, it is nothing to brag about.

Again, Marx had reportedly said, "The soil is nowhere noble in India so that it might not be alienable to commoners!" [Cited, ibid] That also cannot be said at all if the long history of India is well known. The war between kings, the Ashwamedha Yajna and Rajasuya Yajna described in detail in the Ramayana and Mahabharata, was for conquest of newer territories. What is it but a design for possession of additional kingdoms? And it would be a trite to remind that kingdoms incorporated land. Readers must be familiar with the popular saying of Duryodhana - "Without war I shall not dispose of even needle-point amounts of land." So there is no reason to think that whatever information Marx could garner was always true.

As a result, when Lawrence Krader writes, for Marx "the course of Indian history is to be explained by indigenous, not imported categories" [cited, ibid], that is no longer Marxism; it takes on the mantle of straight postmodern and postcolonial thought. The tools of analysis of world history learned from Marxism must be consigned to the museum.

What was the nature of the Arab caliphate in the Middle East if it was not feudalism? In terms of class judgment and relations of production? Which class did the Muslim Shah who defeated Delhi and Ajmer ruler Prithviraj Chauhan belong to? What was Chauhan's class identity? Or, will raising this question be known as "importation"?

Rather, it can be assumed that Marx was more careful when writing the notes to get the facts right. He didn't pay much attention to the truth or to an analysis thereof. Later, if it was to be published in book form, he might have given it fresh thought. But if one who now quotes from those notes and avoids the responsibility of analysis, it is no longer Marxism. And if you want to call these Marx’s thoughts, we shall be the least interested buyers.

[3]

Astute readers will note that all the curiosity and excitement arising from the mega project is only about Marx's new writings. But the title is “The Complete Works of Marx and Engels”. If you look at the workshops of the researchers, it would seem that everything new to know can be found in Marx's new writings. Finding Engels's new works is nothing to dance about. As if, knowingly, it would contain almost all wrong words, there would be mechanical judgment and analysis. So great is their aversion to Engels, and so great is their careless eagerness to express it, that they are at a loss as to what to say when and where.

One such example is right before our hand.

Peter Hudis writes, "Unlike Engels, who tended to uncritically glorify indigenous communal forms in "primitive" societies in his The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State, Marx pointed to the incipient formation of class, caste and hierarchical social relations within them." [Ibid] The references he cites show that this opinion is not his alone, but a collective recipe of this school.

Quite surprising! How could they forget that Engels discussed the classless groups of primitive societies, while Marx considered those ancient peoples among whom class, caste, and stratification had begun? The comparison between the two writers' different judgments about two different populations in two such completely different historical contexts cannot be justified unless with a well-crafted desire to put one blame anyhow. And this is exactly what these research colleagues are doing.

Another episode from the records of Hudis.

A few days before his death, Marx went to Algeria to take rest and for change. There he found to his amazement, whether rich or poor, good or bad fortune makes no distinction between the followers of Muhammad. Their social intercourse is subject to absolute equality, and is in no way affected. We also have similar experience. There is no distinction between the rich and the poor in the prayer line. This is a very good thing. But think now, whether Saudi Arabia's oil Sheikhs consider the Muslims of India or Bangladesh as humans or Muslims at all. Whether there was any response from the Arab sheikhs to the massive attacks on Muslims in various parts of India during or after the Gujarat riots, especially since 2014. Palestinian Muslims have been bombarded to annihilation by Israel for many years. Does it evoke any sense of "absolute equality" (so-called pan-Islamic brotherhood) among the Muslim rulers of Saudi Arabia or Egypt? In fact, the question of class raised by Marx is a very important issue in real social economy and politics. And on this class question there is no effective distinction between Europe and non-Europe. That teaching of Marx is real and important. If we forget that, reading Marx's newly received notes will do us no good.

Now let's talk about an interesting incident.

Marx and Engels -- both became excited about the prospects of a revolutionary movement in Russia in the 1870s after becoming acquainted with Russian left-wing intellectuals, and especially after the publication (1872) of the Russian translation of the first volume of Capital. During that time both of them learned Russian and exchanged long letters with Russian revolutionaries. In so doing they became aware of the mir or village communes in the vast Russian countryside. Engels, however, has no place in the consideration of Hudis or his co-thinkers. They are only interested in what Marx said or wrote. We are also not going to track what Engels also had to say about all of that for the sake of keeping the discussion short. Hudis writes: "While Marx's overall position was closer to that of the Populists [i.e., Narodniks -- A. M.] than the Russian "Marxists" -- who argued, contrary to Marx's own conclusions, that Russia needed to undergo an extensive period of capitalist industrialization before it could be ready for socialism, etc." [Ibid]

What a strange thing.

Serving a bunch of false information and conclusions in one stroke!

One, I had a hard time understanding whom Hudis identified as the Russian Marxists. But surely it cannot be listed by excluding Plekhanov. Let us read what Plekhanov said in 1883 at that very early period: "It goes without saying that neither the author of Capital nor his famous friend and colleague lost sight of the economic peculiarities of any particular country; only in those peculiarities do they seek the explanation of all a country's social, political and intellectual movements. That they do not ignore the significance of our village commune is revealed by the fact that as recently as January 1882 they did not consider it possible to make any decisive forecast concerning its destiny. In the preface to the Manifesto of the Communist Party (Geneva, 1882) they even say explicitly that under certain conditions the Russian village commune may “pass directly to the higher form of communist common ownership”. These circumstances are, in their opinion, closely connected with the course of the revolutionary movement in the west of Europe and in Russia. “If the Russian revolution,” they say, “becomes the signal for a proletarian revolution in the West, so that both complement each other, the present Russian common ownership of land may serve as the starting-point for a communist development." (The Communist Manifesto) It will hardly occur to a single Narodnik to deny that the solution of the village commune question depends on such a condition. Hardly anybody will assert that the oppression by the modern state is favourable to the development or even to the mere maintenance of the commune. And in exactly the same waÿ hardly anyone who understands the significance of international relations in the economic life of modern civilised societies can deny that the development of the Russian village commune “into a higher form of communist common ownership” is closely linked with the destiny of the working-class movement in the West. It thus turns out that nothing in Marx’s views on Russia contradicts the most obvious reality, and the absurd prejudices concerning his extreme “Occidentalism” have not the slightest trace of reasonable foundation.” [Plekhanov 1976, 69] Here, it appears, within a year Plekhanov had recalled and expressed satisfaction with what Marx and Engels had written in the joint preface to the Russian version of the Communist Manifesto (not at all different from Hudis's statement). Not only this, Plekhanov had also opposed those who saw Euro-centricism in Marx more than a century before the modern Marx-worshippers.

Second, the Russian Marxists did not speak of the necessity of any long sequence of capitalist industrialization before socialism at all. Neither Plekhanov, nor Lenin. Narodniks argued that capitalism was not possible in Russia due to the existence of the village communes. To them, these Marxist leaders tried to show in their respective times whether capitalism is possible or impossible - this question no longer arises; a capitalist agrarian economy is already developing in Russia, even in the countryside. Especially on the basis of this analysis, Lenin brought forward the question of building the unity of Russian muzhiks with the Russian proletariat. And in fact, within a month of the bourgeois democratic revolution of February 1917, Lenin called for a socialist revolution in his April Theses. These are now so well known that only "I shed tears for I don’t see the path with my eyes shut" in the words of the poet Tagore explains their case -- otherwise there would be no room for the above accusations of Hudis about the Russian Marxists.

Third, in practice, after the socialist revolution, it was found that the mir or the village commune was of no use. Even eleven years before the revolution, it was not possible to call for the establishment of collective farms and take up the programmme. Not only that, even after starting the collective farm movement from 1928, the number of state farms could not be very large for a long time. As a result, regardless of what Marx and Engels thought or understood when they spoke to the Narodniks, that idea was of no use after the revolution. There was a little lump in that thought. Not only because Engels thought wrong, Marx also got it wrong that day. Although in the 1870s it may not have been so unusual to make that mistake.

But today we have to write these words in the year 2025, it is really surprising!

[4]

Coincidentally, another of Peter Hudis's writings recently came to hand — “Thoughts on Marx, Marxism, and Culture” — from a member's mail in the form of a thread in an online email discussion group called the Marx Forum. However, this is not a complete article. Some of his views are expressed in the ongoing discussion of that group. But even in that he raised some things, which deserve to be judged in the light of Marxism as per our perceptions.

There, Hudis seeks to undermine the position of Friedrich Engels and other prominent Marxist thinkers in support of Karl Marx's statement on culture. In the beginning he has cited a paragraph from the first volume of Marx Theories of Surplus Value: “Humanity itself is the basis of material production, as of any other production that it carries on. All circumstances, therefore, which affect man, the subject of production, more or less modify all his functions and activities, and therefore too his functions and activities as the creator of material wealth, of commodities. In this respect it can in fact be shown that all human relations and functions, however and in whatever form they may appear, influence material production and have a more or less decisive influence on it.” [Marx 1969, 288].

This professor knows that the above statement by Marx does not fit the much-discussed structure-superstructure analytical model of Marxism. He also knows that Marx published his 1859 Contribution to a Critique of Political Economy In a very famous paragraph in the Preface to the book, he wrote down his statement about superstructure in the form of a thesis. He never corrected this statement, or said that what he had written there was wrong or at least biassed. The next clearest expression of this thesis remains in a footnote to the first volume of Marx's Capital published in 1867 (referred to by Hudis) and again two pages later (which he no longer notices, or, if he does see, he inadvertently ignores). [Marx 1974, 86 and 88] But so what? He could not contain his joy that Marx did not refer to it again in any of his political works. Rather, he took the above-quoted statement as Marx's original opinion and criteria, and took the initiative to transfer Marx's well-known thesis on superstructure on the shoulders of others (especially Engels) and purge the onus from Marx. He then solemnly told us, “Nevertheless, the formulation was codified as a central principle in Engels’ late writings (after Marx’s death) and was promoted as part of a photocopy theory of knowledge by Plekhanov, Kautsky, the early Lenin, and many others who claimed to follow in their footsteps.”

However, he is willing to make some concessions to Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, and wrote it in brackets: “In his “Abstract of Hegel’s Science of Logic” of 1914 Lenin broke from this vulgar materialist approach, which he had advanced six years earlier in Materialism and Empirio-Criticism, writing "Man's consciousness not only reflects the objective world, but creates it". His only sorrow is, “Lenin of course never published his philosophic notebooks, and the base-superstructure relation was largely interpreted in a casual-determinist manner, by orthodox Marxists, with the economic base posited as the independent variable and the superstructure as the dependent one.”

Lenin had provided a trenchant criticism of Machism and Mach's Russian followers in Materialism and Empirio-Criticism. Whether or not he cultivated gross materialism there, we will not enter into that debate in this essay. I have previously written in detail about the position and contribution of Lenin's work to Marxist literature in a Bengali book. [Mukhopadhyay 2023]

Let's take a look at what Marx said about base and superstructure:

“My inquiry led me to the conclusion that neither legal relations nor political forms could be comprehended whether by themselves or on the basis of a so-called general development of the human mind, but that on the contrary they originate in the material conditions of life, . . . The general conclusion at which I arrived and which, once reached, became the guiding principle of my studies can be summarised as follows. In the social production of their existence, men inevitably enter into definite relations, which are independent of their will, namely relations of production appropriate to a given stage in the development of their material forces of production. The totality of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real foundation, on which arises a legal and political superstructure and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness. The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness.” [Marx 1977, 20-21; emphasis added]

What Marx says here is quite clear.

Did Marx later change his position?

No. Rather, eight years later, in a footnote in the first volume of Capital (1867), he again reminded the reader of these words. An American newspaper writes that his above thesis is true only for capitalism, but not for medieval or ancient societies. Marx wrote in reply: “In the estimation of that paper, my view that each special mode of production and the social relations corresponding to it, in short, that the economic structure of society, is the real basis on which the juridical and political superstructure is raised, and to which definite social forms of thought correspond; that the mode of production determines the character of the social, political, and intellectual life generally, all this is very true for our own times, in which material interests preponderate, but not for the middle ages, in which Catholicism, nor for Athens and Rome, where politics, reigned supreme. In the first place it strikes one as an odd thing for any one to suppose that these well-worn phrases about the middle ages and the ancient world are unknown to anyone else. This much, however, is clear, that the middle ages could not live on Catholicism, nor the ancient world on politics. On the contrary, it is the mode in which they gained a livelihood that explains why here politics, and there Catholicism, played the chief part. For the rest, it requires but a slight acquaintance with the history of the Roman republic, for example, to be aware that its secret history is the history of its landed property. On the other hand, Don Quixote long ago paid the penalty for wrongly imagining that knight errantry was compatible with all economic forms of society.” [Marx 1974, 86f; emphasis added]

Two pages later he reiterates this thesis: “This juridical relation, which thus expresses itself in a contract, whether such contract be part of a developed legal system or not, is a relation between two wills, and is but the reflex of the real economic relation between the two. It is this economic relation that determines the subject-matter comprised in each such juridical act.” [Marx 1974, 88; emphasis added]

A second German edition of this book appeared in 1973 during Marx's lifetime. Even there these statements remain intact.

As a result, there is no way to assume that it is a manipulation of Engels or a misinterpretation of Plekhanov, as Hudis said! Why not, both German versions of it were supervised by Marx during his lifetime.

Fortunately, one of our Bengali only-Marx intellectual, Pradeep Bakshi, however, has opened a way. The English translation of Capital came out after Marx's death (1884) and there, under the guidance of Engels, Marx's original statements were changed in many places. So the original German certainly doesn't have that. Those who know the German language, can open the original German text and compare this place.

I thought so at first too. Later I thought, let me have a try. I learned a little bit of the German language at one time. The German version of the first volume of Capital can be found on the Internet.

Lucky for me, I found it by searching the net with the help of Google. As it turned out, in the corresponding place of the very early (1867) German edition, Marx had written a statement, which Engels' disciples translated into English in an immaculately literal way: "Diess Rechtsverhältniss, dessen Form der Vertrag ist, ob nun legal entwickelt oder nicht, ist nur das Willensverhältniss, worin sich das ökonomische Verhältniss wiederspiegelt. Der Inhalt dieses Rechts-oder Willensverhältniss ist durch das ökonomische Verhältniss selbst gebel." [Marx 1867, 45]

That is, Marx defended his thesis very carefully.

[5]

So there are many problems with this statement by Comrade Peter Hudis that he did not notice.

As a leading intellectual in the West, he must have known, there is some moral obligation to quote someone, even to make an allegation or quote someone's name without quoting them. Be sure about what you are saying, whether you are saying it right or not. You should ensure the person you are talking about has really said that. I want to remind them one by one.

First, in the manuscript of the philosophical book called The German Ideology, which Karl Marx wrote together with Friedrich Engels in 1845-46, they had almost identical statements, although they did not mention them as superstructures. "This conception of history thus relies on expounding the real process of production — starting from the material production of life itself — and comprehending the form of intercourse connected with and created by this mode of production, i.e., civil society in its various stages, as the basis of all history; describing it in its action as the state, and also explaining how all the different theoretical products and forms of consciousness, religion, philosophy, morality, etc., etc., arise from it, and tracing the process of their formation from that basis; thus the whole thing can, of course, be depicted in its totality (and therefore, the reciprocal action of these various sides on one another). It has not, like the idealist view of history, but remains constantly on the real ground of history; it does not explain the formation of ideas from material practice,” etc. [Marx and Engels 1976, 61]

And further, “The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas: i. e., the class which is the ruling material force of society is at the same time its ruling intellectual force. The class which has the means of material production at its disposal, consequently also controls the means of mental production, so that the ideas of those who lack the means of mental production are on the whole subject to it. The ruling ideas are nothing more than the ideal expression of the dominant material relations, the dominant material relations grasped as ideas; . . .” [Ibid, 67]

If it was not acceptable to him for Engels had a touch ther5ein, he should have said so. It should not have been ignored.

They raised the same argument in the Manifesto of the Communist Party in 1948: “Does it require deep intuition to comprehend that man’s ideas, views and conceptions–in one word, man’s consciousness–changes with every change in the conditions of his material existence, in his social relations and in his social life? What does the history of ideas prove than that intellectual production changes its character as material production is changed? The ruling ideas of each age have ever been the ideas of its ruling class.” [Marx and Engels 2014, 181]

It was basically written by Marx and written on some strictly political topics. It is worth noting that Marx and Engels' joint contributions to the publication of translations of the Communist Manifesto in various languages up to 1882 have been published, and in them they have at times acknowledged the various errors and limitations of the document's statements. Neither they nor Marx alone advocated any reformulation of the basis-superstructure relationship. That is to say, for almost forty years, Marx wanted to keep the reader of his various works aware and alert about this basic proposition.

Second, Peter Hudis had better informed us, if after Marx's death, Engels had really codified Marx's above thesis in any of his works – and where. We have never seen anything like it. Engels refers to many of Marx's statements in many places as a sign of his gratitude to Marx, but with a different emphasis, or rather, with more importance than Marx, in many of his well-known printed works of the period 1883-95. We could have benefited if Hudis had provided proper references.

Rather, thirdly, what we actually know is something to the contrary. At a time (from the late 1880s until his death) when most European communist intellectuals were mechanistically reducing Marx's basis-superstructure thesis to economic determinism, it was Engels who warned against it in at least five major letters. [Marx and Engels 1982; Letters dated 5 August 1890; 21-22 September 1890; 27 October 1890; 14 July 1893; 25 Januari 1894]

Let me quote from a single letter dated 21-22 September 1890 written to Joseph Block:

“According to the materialist conception of history, the ultimately determining factor in history is the production and reproduction of real life. Neither Marx nor I have ever asserted more than this. Hence if somebody twists this into saying that the economic factor is the only determining one, he transforms that proposition into a meaningless, abstract, absurd phrase. The economic situation is the basis, but the various elements of the superstructure—political forms of the class struggle and its results, such as constitutions established by the victorious class after a successful battle, etc., juridical forms, and especially the reflections of all these real struggles in the brains of the participants, political, legal, philosophical theories, religious views and their further development into systems of dogmas—also exercise their influence upon the course of the historical struggles and in many cases determine their form in particular. There is an interaction of all these elements in which, amid all the endless host of accidents (that is, of things and events whose inner interconnection is so remote or so impossible of proof that we can regard it as non-existent and neglect it), the economic movement is finally bound to assert itself. Otherwise the application of the theory to any period of history would be easier than the solution of a simple equation of the first degree.” [Marx and Engels 1982, 394-95]

Does anyone here see anything about the superstructure as a photocopy of the economic basis? Similar statements will also be found in the other letters mentioned above.

Fourth, Joseph Stalin, whatever our other accusations in other respects, in his Marxism and Problems of Linguistics, argued against seeing the relationship between base and superstructure as a mechanical, one-to-one correspondence. His statement was: "Further, the superstructure is a product of the base, but this by no means implies that it merely reflects the base, that it is passive, neutral, indifferent to the fate of its base, to the fate of the classes, to the character of the system. On the contrary, having come into being, it becomes an exceedingly active force, actively assisting its base to take shape and consolidate itself, and doing its utmost to help the new system to finish off and eliminate the old base and the old classes.” [Stalin 1976, 5; emphasis ours]

So, Hudis's allegation — "The notion that the "superstructure"—politics, civil society, juridical relations, culture, religion, etc.—is a mere reflection of the economic base became a virtual article of faith among innumerable post-Marx Marxists"— is without any real factual ground. No, he has simply put these words in others’ mouths. Maybe unknowingly. Owing to a blind inclination. Or he may have heard from others, without verifying with his own hands.

So based on the above survey we can now claim, nowhere had Engels, Plekhanov, Lenin, Stalin, and other Marxist leaders presented a “photocopy theory of knowledge”. If his objection remains to the very word "reflection" to denote the act of thinking — quite allowable, there is nothing wrong with that — then he should begin his criticism verily with Marx. Marx, in his Afterword to the second German edition of the first volume of Capital, very clearly characterizes thought as the reflection of the external world to the brain. That statement is too well known to be cited here.

But no, we note with great surprise that these only-Marx scholars prefer to quote from Marx's unpublished writings. I don't know if it is because of the difficulty in most cases, they avoid Marx's published works as much as possible. And where the statements of Engels or others coincide exactly with a well-known printed statement of Marx, which these authors dislike, they prefer to forget Marx's involvement.

Could this be a method of discussion??

[6]

I don't know if Comrade Hudis noticed, Karl Marx is also wrong in many places. We usually don't mention them because it's not necessary. Marx's correct statements are so vastly numerous that it takes us a lifetime to absorb them, so we don't have the time or opportunity to bother with a couple of minor mistakes. But a mistake is still a mistake. For example, despite his correct criticism of Malthus's theory of population, Marx’s satirical criticism of its application by Darwin in his theory was factually incorrect. To please Hudis, Engels made the same mistake. Perhaps as a result of the influence of Marx's ideas.

The same is true of what Hudis quotes at the beginning of his above essay from Marx’s Theories of Surplus Value – which was unpublished in his life time. Any careful Marxist reader will understand that Marx's words are wrong here. Had this book been published during his lifetime, I think he would have changed this statement. He would correct the statement in accordance with his main thesis regarding structure and superstructure. For that thesis is one of Marxism's main pillar. Apart from this, no general explanation of the major political events of a long period of world history stands. And if it is accepted, the state, religion, politics, wars, revolutions—all historical events — become subject to an intelligible explanation. However, in the interpretation of art, literature, music, etc. one has to be more cautious. To intelligent and informed Marxists the world over, these are all ABC.

That's why I shall remind Hudis, who also quotes from an important work of the Czech philosopher Karel Kosik. (I am deeply grateful to Comrade Hudis for drawing my attention to this important book), that it is actually a variation of Engels' statement. And if you read that book well, you will find some forceful statements in support of Marx’s basic thesis. For now, let's just give a quote. Kosik first accepted Plekhanov and Labriola's variant of the distinction between economic factors and economic structure, although he disagreed with their interpretation. [Kosik 1976, 61-62] Then he said: ". . . the economic structure will continue to maintain its primacy as the fundamental basis of social relations." [Ibid, 63] And a little further he reminded, "Materialist monism [= Marxism] considers society to be a whole which is formed by the economic structure, i.e., by the sum total of relations that people in production enter into with respect to the means of production. It can provide a basis for a complete theory of classes, as well as an objective criterion for distinguishing between structural changes that affect the character of the entire social order, and derivative, secondary changes that only modify the social order without fundamentally altering its character.” [Ibid, 64]

That is, if the quotation of Marx is taken to be true, you cannot quote from Kosik; on the other hand, if you decide to refer to Kosik’s views on the matter, Marx's unpublished statement during his lifetime cannot be accepted, far less cited.

The trouble is, Hudis and thinkers like him are getting into such a trap of inconsistency by erecting their Marxian ideology on a Marx-only pillar. We hope that those who are listening to these authors and nodding in agreement will also think about the matter better and compare it from all sides.

[7]

We are almost done. To expose all the fallacies of the author in question would consume many words and would most likely be a terrible torture on the patience of the readers. We find Peter Hudis' original idea wrong, and without doubting the motives of those from whom he is gathering material and direction I am compelled to dismiss the statement. Marx and Engels comprise the original structure of Marxism. Marx was its chief thinker, Engels its first truly popularizer and commentator with much of his original thinking. Unless Engels is taken alongside Marx or consciously excluded in regard to every socio-economic or scientific question, we will have to go with a half-baked Marxism in almost everything, which will not be of any use in socio-political movement.

A natural question is bound to arise in the minds of many: Why are all these Marx-only intellectuals running after such a misrepresentation? What do they really want?

We do not yet assume that they have any ulterior motives. We want to see their tendency as a distraction. They seek to overcome the criticisms of earlier Marxist thinkers about the "evolution-Marxism" and present Marx primarily as a liberal humanist sociologist and historical analyst. Class Party Class Struggle Revolution Social Change – These are not the real agenda of real Marx. Marx was a brilliant thinker. He has worked all his life chasing new problems. Solving problems, finishing work – such events do not exist in his life. So none of his works are finished, not complete. Unfinished incompleteness is the glory of all his works. This is where Engels left off. In the statement written by a Greek professor in the American Marxist Human Geography magazine, "The main reason why Engels has attracted so much rancor is that he systematized Marxism as a theoretical system and transformed it to a mass political movement. This is his 'cardinal sin' and for this contemporary anti-Engelsionists practically prefer that Capital should not have been published: 'it is an unfinished and unfinishable work'." [Mavroudeas 2020] The author's opinion about all these intellectuals is, "The common ground uniting them is their abhorrence for the existence of Marxism as a coherent theoretical tradition and as a weapon for the revolutionary struggle of the working class for the emancipation of human society." [Ibid, abstract]

One might think, we are exaggerating. No, it will be clear from the title and/or synopsis of some of the experts' works. Marcello Musto wrote an article some time ago (2009) titled “Karl Marx: The Indiscrete Charm of Incompleteness”. At the end of that article he wrote, "After many seasons marked by deep and reiterated misunderstanding of Marx, resulting from the attempted systematization of his critical theory – given its originally incomplete and non-systematic character – by the conceptual impoverishment which has accompanied its popularization, by the manipulation and censorship of his writings, and the instrumental use of the same for political purposes, the incompleteness of his work stands out with an indiscrete charm, unobstructed by the interpretations which had earlier deformed it, even manifestly becoming its negation. From this incompleteness re-emerges the richness of a problematic and polymorphous thought and of a horizon whose distance the Marx Forschung (the research on Marx) still has so many paths to travel.” [Musto 2009]

Another Marx-only scholar, Michael Heinrich, echoes the same tone in the last line of a recent essay: “Marx’s legacy is not a finished work, but rather a research program, the vast outline of which are only now becoming visible through MEGA.”

The biggest crime of Friedrich Engels is to develop a scientific and ordered doctrine called Marxism by editing and publishing Karl Marx's haphazard manuscripts in a coherent form. From the mega-project, they are now bringing forward those unfinished manuscripts of Marx and trying to impress the reader, see how great a thinker our Karl Heinrich Marx was. What a wonderful mess of his writing! How beautiful are his unfinished sentences, incoherent paragraphs, ill-connected chapters! What a wonderful indecisiveness of each of his works!!

I have only one query. Almost a hundred Marx-only intellectuals are singing the praises of incompleteness, indecision, chaos in Marx's work so loudly – why do they themselves not write an article following the great Marx-genius? Why are all their articles published in organized form? Is it purely out of modesty to keep Marx forever unique?

[8]

The main theoretical pillars of Marxism are as follows: 1) materialism, 2) dialectics, 3) class struggle, 4) dictatorship of the proletariat, 5) relations of production and productive forces, 6) labor theory of value, 7) surplus value, and 8) basis-superstructure – relations and conflicts. In each of these cases, to understand Marx's statement, one must resort to Engels's interpretation, and based on that, the correct concept will be developed. Then read as much as you can, Plekhanov, Lafargue, Labriola, Lenin, Stalin, Trotsky, Bukharin, Gramsci, Mao, Hoxa, Castro, etc., learn from different perspectives, identify and analyze the differences between them, etc. At the same time, you may also read the works of "Marx-only" scholars following the Mega-II project. During that reading, be sure to note who is making favourable statements about the above key concepts and who is trying to -- knowingly or unknowingly, deliberately or without motive -- hide some of them. Anyone who tries to separate one or more of its conclusions from Marx's thought with the help of various pretexts, has not understood Marxism. Know that it is not Marxism. Not Marxist thought. Not, even though there are quotations from various unpublished notes of Marx.

Karl Marx is no prophet to us, communists. Not to speak of the last and only Prophet!!

It is time to be careful about all these things.

References

Ashoke Mukhopadhyay (2019), Marxism and Friedrich Engels: Looking Back (in Bengali); Bahubachan Prakashoni, Kolkata.

Peter Hudis (2004), "Karl Marx among Muslims"; Original source: Capitalism Nature Socialism, Vol. 15 Number 4 (December 2004)

Michael Heinrich (2016), “‘Capital’ after MEGA: Discontinuities, Interruptions and New Beginning”, Crisis & Critique Vol. 3: Issue 3.

Stavros Mavroudeas (2020), “Frederick Engels and His Contribution to Marxism”; Human Geography, 2020.

Karel Kosík (1976), Dialectics of the Concrete, Dordrecht-Holland: D. Reidel, 1976.

Karl Marx (1969), Theories of Surplus Value, Part 1 [1861-63]; Moscow: Progress Publishers.

Karl Marx (1974), Capital, Vol. I; Moscow: Progress Publishers.

Karl Marx (1867), Das Kapital, Band I; from Internet Archive: visit – https://archive.org/details/daskapitalkritik67marx/page/n3/mode/2up

Karl Marx (1977), A Contribution to a Critique of Political Economy; Moscow: Progress Publishers.

Karl Marx and Frederick Engels (1976), The German Ideology; Moscow: Progress Publishers.

Karl Marx and Frederick Engels (2014), The Communist Manifesto; New Delhi: Grapevine India.

Karl Marx and Frederick Engels (1982), Selected Correspondence; Moscow: Progress Publishers.

Mecello Musto (2009), “Karl Marx: The Indiscrete Charm of Incompleteness”; Review of RadicalP olitical Economics, Volume XX, No. X.

G. V. Plekhanov (1976), Socialism and the Political Struggle; Selected Philosophical Works, Vol. 1; Moscow: Progress Publishers.

Joseph Stalin (1976), Marxism and Problems of Linguistics; Peking: Foreign Languages Press.

0 Comments